Introduction

This article has been written with two aims in mind. The first was

to summarize what is known about my forbears, on both my father’s and

my mother’s side. The information presented derives partly from notes

which my parents either inherited or wrote themselves, and partly from

memorized conversations with them. The second objective was more

broadly based.

The surname Staveley cannot be described as fairly The surname Staveley cannot be described as fairly common on the one hand, or as very rare on the other. But there seems to be a sufficient number of Staveleys in existence to regard them as forming

a group analogous to a clan, though lacking the ancentral or patriarchal

head who presides over a Scottish clan. A Staveley might well wonder if

there is any connection between his own family and one or more of other

branches or families of the clan. The chance of achieving some success in

seeking such connections would largely depend on how lucky the seeker

was in discovering new facts, but at least the total number of members of

the clan should not be so great as to make such an investigation

ridiculous. I therefore thought it worthwhile to collate and present what

information I could muster about Staveleys in general. Some of this has

come from published works, but a substantial portion – which perhaps

provided the more interesting facts – has really reached me just by chance.

With regard to my mother’s lineage, almost nothing is known about

her father. Her mother’s maiden name was Cleobury, pronounced

Clibbery, and relatively little is known about the Cleobury family.

Accordingly, the reason why the treatment of this family, which follows

that of the Staveleys, occupies less space is simply that there is less to

say about the Cleoburys. There has been absolutely no question of

discrimination.

I hope that what follows will be of some interest to some present and

future members of the family, and perhaps even of some slight help to any

one of them contemplating a serious genealogical study.

The origin of the name Staveley

Staveley is a place-name. There are four places so named in England.

The largest is that in Derbyshire, a few miles north-west of Chesterfield

and not far from the Yorkshire border. There is a Staveley to the south of

Ripon, a mile or so from the A6055, which puts it quite near places with

Staveley associations, as we shall see. Another is that in Cumbria Gn

the part which used to be Westmorland), familiar to many visitors to the

Lake District as it lies a few miles to the east of Windermere on the A591.

Finally, there is Staveley-in-Cartmel, north-west from Grange-over-Sands

and near the junction of the A590 and A592.

All four places are settlements of considerable age. They are all to

be found in thirteenth century records, and the Derbyshire and Yorkshire

Staveleys appear in the Domesday Book (1086). As is to be expected, a

variety of spellings turns up. The Concise Oxford Dictionary of English

Place Names gives the following (besides the ‘correct’ version):- Stavelie,

Staveleia, Stavelay, Stavele, Stanlei, Staflea and Staveleie. Rather

surprisingly, the Stavely so often inflicted on modern bearers of the name

is not in this list. All forms of the name have their origin in the Old

English ‘staef-leah’, ‘a wood where staves were got’.

The geographical distribution of Staveleys in England

All four places having the name are in northern counties. Since for

most people in earlier times life was relatively localized, no doubt for a

long while Staveleys tended to be concentrated in the north. Indeed, this

still seems to be true. The pedigree of our branch of the family, as far

as it is known, starts in the eighteenth century in north-east Yorkshire, a

county where the surname is more common to this day than in, say,

southern England. Thus, there are only ten Staveley entries in the current

edition of the London telephone directory, whereas there are twenty in the

directory covering York and its immediate neighbourhood, and seven in

the corresponding directory for Harrogate. In the directory which covers

Oxfordshire and part of Berkshire there are three Staveley entries

(including mine), plus one example of Staveley contributing half of a

double-barrelled name, in this case Staveley-Parker.”

Even though the Staveleys were concentrated in the north, and in

spite of the difficulties in travelling in medieval times, some

enterprising Staveleys must have moved south. In the church at Bicester,

13 miles from Oxford, there is a memorial brass (on the left of the altar)

to William Staveley, dated 1498. (We shall see that William has been a

popular choice of a Christian name for a Staveley). Later on, I shall have

a little to say about Staveleys in the seventeenth century in London and.

Leicestershire. Some must have emigrated. There have been Staveleys for

some time, for example, in Ireland, New Zealand, and the U.S.A.

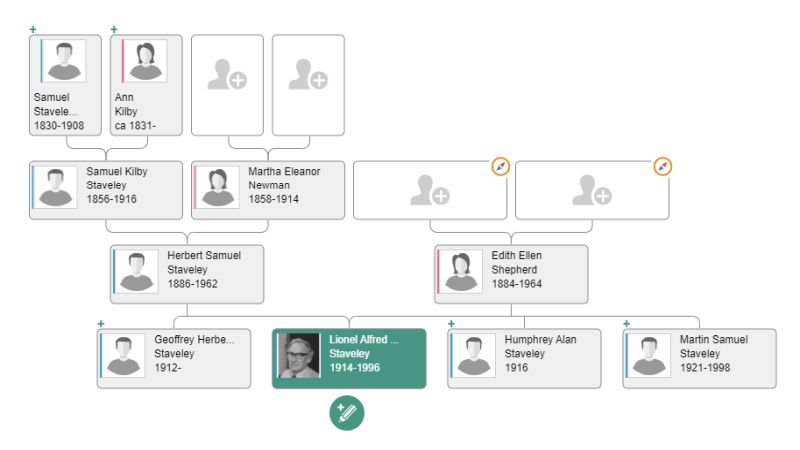

Our own branch of the Staveleys

Our certain knowledge of this begins with Samuel Staveley, born in 1788 in

the village of Harpham, which is roughly midway between Bridlington and Great Driffield, and a little south of the A166 which joins these two towns. It is remarkable that although

It may be noted that telephone directories could be used, with a

little effort, to make an approximate estimate of the size of the Staveley

clan, i.e. of the total number of people in England with this surname. It

would be a matter of finding the total number of entries in the directories

covering a suitably large region (e.g. by multiplying the total number of

pages by the average number of entries per page), and combining this with

the appropriate population statistid to give the average number of

individuals per entry, and then multiplying the total number of Staveley

entries by this factor.

Samuel Staveley fathered nine children, only one of these continued the

male line, and then just one son continued the succession in each of the

next two stages. It is at once obvious that anyone seeking a connection

between our branch of the family and another must begin the backward

search in the second half of the eighteenth century. The frequency of the

name of Samuel is noteworthy, and this might be of some help in attempts

to discover who preceded Samuel Staveley of Harpham.

This Samuel Staveley, who heads the family tree in Appendix 1, died

at the age of 47, leaving six small children. It is believed that the

widow and her children left the Great Driffield district and settled in

London, effectively losing touch with any Yorkshire relations. It would

certainly seem that the son Samuel, who was to continue the male line,

was far from the north when he married Ann Kilby, as she was generally

known in the family as Ann of Woodstock. (Ann, the source of my own

third Christian name, was the fourth of the eight children of Edward and

Charlotte Kilby, who were married in Oxford in 1824).

My parents seemed to regard Great Driffield as the centre of the

region associated with the family in time past, but it appears that the

local Staveleys resided in nearby villages rather than in Driffield itself,

and still do. There are Staveleys now living in the villages of Wetwang,

Nafferton and Tibthorpe (or at least there were quite recently), which are

all within a few miles of Great Driffield. In the eighteenth century, and

perhaps earlier, there appear to have been Staveleys residing in Market

Weighton, which is a little further from Driffield, being west of Beverley

on the A1079.

My parents

I have no intention of presenting potted biographies of any living

Staveleys, but it might perhaps be of some interest to younger members of

the family to know a little about my parents. Both were ‘only children’,

and both grew up in London. in fact, in the City of Westminster.

I imagine that their homes, especially that of my mother, ran on a fairly

tight budget. Her own mother was widowed when my mother was about five,

and although my grandmother received a pension I believe this was rather

meagre, and had to be supplemented by her earnings from a part-time job

with a local church.

The schools my parents attended still exist. My father went to Westminster City School (not to be confused with the famous Westminster School next to the Abbey), and my mother to the Grey Coat Hospital. I think they both left school at the age of sixteen or so, my mother having acquired a love of English history which remained with her all her life. She took a course in shorthand and typing, and until she married had a secretarial job with a firm. Her employer seems to have been a benevolent man. On one occasion, observing that my mother looked rather ‘run down’, he hold her to take a seaside holiday, and gave her five pounds to cover all expenses.

My father became a Civil Servant in the Customs and Excise Department. He began as an Officer at the age of twenty-one, and his first permanent posting took him to Stamford in Lincolnshire, where my parents were to live for the next twenty years and where my brothers and I were born and went to school. Promotion of my father to the next rank of Surveyor meant, at that time, his taking a competitive examination at which candidates were allowed two attempts, with approximately a one in ten chance of passing. A rather small house containing four boys is not the ideal place in which, at the age of forty or so, to study in one’s spare time for an examination, but my father made it as at his second attempt, and in due course the family left Stamford. He held positions in Grimsby, Birmingham and London, and for the last five years of his career was Acting Higher Collector at the Customs and Excise Office in central Birmingham.

On his retirement, in 1946, my parents moved to Hunstanton in Norfolk, where my father created and maintained a garden with reasonable success, bearing in mind that the garden faced north, was only about two hundred yards from the cliff edge, and was virtually unprotected from the often icy winds coming off the North Sea.

Both my parents were fond of music. My mother sang (contralto), and my father was a competent pianist and organist. He was organist and choirmaster for some ten years (the nineteen twenties, effectively) at St. Mary’s Church in Stamford. This church stands on the road through the town which, before the days of by-passes, was the A1, known as the Great North Road. (It was so much admired by Sir Walter Scott that it is said that he always took off his hat to it when passing it on his journeys by stage-coach between Scotland and London). A feature of my father’s time at St. Mary’s was that he organized (no pun intended!) the performance of several oratorios, which included Mendelssohn’s St. Paul and Hymn of Praise, Gounod’s Redemption, and an abridged version of Haydn’s Creation. The orchestra which he conducted was composed of local amateurs, but professionals were engaged to sing the solo parts.

The man whom many would regard as Britain’s most talented living composer, Sir Michael Tippett, was educated at Stamford School. He had piano lessons from a lady in the town with the apposite name of Mrs. Tinkler. Tippett has described in an interview how at that time he was quite ignorant of some aspects of musical theory, and felt that he ought to do something about this. So he asked Mrs. Tinkler who might be able to help him, and she advised him to approach the organist of St. Mary’s. He went to see my father, who expressed willingness to give him some. tuition, but the question of payment for this posed a problem as Tippett, (then about seventeen), had no money to spare. So they agreed that, instead of paying for the lessons, and notwithstanding a leaning on Tippett’s part towards agnosticism or atheism, he would sing in the choir at St. Mary’s, which was rather thin on the adult side at the time. I read Tippett’s account of this incident long after my father’s death, but I remember him once telling me that he had given the young Tippett some lessons in the theory of music.

As a result of the salary increase which went with my father’s promotion to the rank of Surveyor, he was able to rent a house superior to that in which we had lived hitherto. This latter was a three-bedroomed semi-detached house, no.45, Queen Street, in which my three brothers and I slept in one room. The move to the seventeenth century house, 40, St. Martins, where the family spent its last five years or so in Stamford, doubled the number of bedrooms and more than doubled the area of the downstairs rooms. (It was later converted into two residences). The rent my father paid for it (to the Burghley Estate) was £60 per annum. St. Martins is perhaps the most beautiful street in an attractive town. In 1977, the Royal Commission on Historical Monuments published a volume wholly devoted to Stamford. It contains several photographs of buildings in St. Martins, including one showing part of no.40.

Correspondence with Staveleys of other branches of the family

I have twice in my life received letters, quite out of the blue, signed by a Staveley unknown to me. The first reached me at Oxford during my first year (1932/3) as an undergraduate at Trinity College. The writer was a Tom Staveley, a master at Tonbridge School, who had himself been at Trinity before the First World War. He said that he had seen my name on a list of new members of the College, and as he was very interested in his personal genealogy he was writing to see if there might be a link between his family and mine. In reply, I told him that I would pass his letter on to my mother, as she would be of more help than I could be. They duly exchanged letters, and in one of his he gave his pedigree. Unfortunately, the copy of this has not survived, but I do remember that his family tree began with the entry “William Staveley. artist, of York, b.1760′. Tom Staveley said he thought it was ‘obvious’ that his branch of the family and ours were linked together ‘at some remote date’. He pointed out that in his branch the traditional names for the men were Tom and George (I’m surprised that he didn’t mention William), while the Samuel so frequently encountered in our branch was completely absent from his. He added that he proposed to send the copy of our family tree which my mother had provided to his cousin, Admiral Cecil Staveley, as he was more of an authority on genealogical matters than he was. In the current edition of Who’s Who, there is an entry for Admiral William Staveley, who was born in 1938 and is the son of an admiral, who in all probability was Tom Staveley’s cousin Cecil.

The second totally unexpected letter came from New Zealand in the early nineteen forties, i.e. during the Second World War. The writer was a farmer, who said he believed that there was a Staveley residing in Oxford, and would that be me, and if so might I be a relative of his, even if a distant one. His syntax was a little shaky at times, but from the way he expressed himself it seemed that the Staveley resident in Oxford whom he had in mind was an elderly spinster, who had lived in Oxford but who had died a few years before, I wrote to him and told him what I could about my forbears, which prompted him to reply with a much longer letter than the first. This began ‘Dear Stave’. (The only other example I have encountered of this abbreviation is on my driving licence). In this second letter he had a remarkable story to tell. But before I disclose this, I have to confess of having made a mistake which I have always regretted. Knowing Tom Staveley’s considerable and genuine interest in Staveley genealogy, I sent the New Zealander’s letters to him without making copies. Of course, I asked that the letters should be returned to me, but I never saw them again. I got in touch with his son, who had also been at Trinity College, and he reported, very apologetically, that he had searched through his father’s papers for the missing letters but without success. I later learnt that his colleagues at Tonbridge School regarded Tom Staveley as an eccentric character, and that the eccentricity had increased with age. Accordingly, what I have to say about the contents of the New Zealander’s letters comes entirely from my memory.

The story involves one of England’s well-known stately homes, namely Harewood House, roughly midway between Leeds and Harrogate. The owner of the house and estate is the Earl of Harewood, and the family name is Lascelles. The present family has a connection with the Royal Family, in that the wife of the Earl earlier in this century was Princess Mary, the only daughter of George V. According to my New Zealand correspondent, this property originally belonged to a Staveley family. But unfortunately one of the Staveley owners died at a fairly early age, leaving a widow with two young sons, one of them named Miles. A Lascelles then enticed the widow into marrying him, and he had the two boys deported to Ireland – I think it was to the south of that country. This account of how the Lascelles acquired the estate ended in the letter with the sentence ‘So they didn’t get it honest’. The writer then went on to say that he possessed a few family relics, which included the seal. He gave some details about the cost of arms which I can’t recall, but I do remember that he said that the accompanying motto was ‘Fidelis ad urnam’, i.e. ‘faithful to the (funeral) urn’, or, one might say, ‘faithful to the grave’.

This was the last letter I had from the New Zealand Staveley. But not long afterwards we received from him several pounds of dripping, a welcome gift in wartime when stringent food-rationing prevailed. There are certainly Staveleys in New Zealand today. One of them appears in the current ‘Who’s Who’. He is Sir John Staveley, a highly regarded member of the medical profession to judge from the honours and decorations he has received. He was born in 1914, the son of William Staveley, and has one son and one daughter.

The story that the Staveleys had been dispossessed by a roguish Lascelles may seem rather fanciful, but I would like to add two pieces of information which may have some relevance. The first results from a recent meeting with an old friend of mine, by name John Moy, who told me that, having retired, he had been carrying out research into the genealogy of his family. Knowing that he had relations, if distant ones, in Ireland, he had sought the help of a friend there to investigate the Irish branch of his family. This contact recently reported his findings to John, and in connection with the coat of arms of the Irish side of th Moy family he had written: “The motto is ‘Fidelis ad urnam, which is also the motto of the Irish Staveleys’. My second comment is simply that my father once told me that there was a belief in his family that one of his forbears (I don’t know which) could have laid claim to a substantial inheritance in Yorkshire, but that he was a rather stubborn person, and in spite of attempts to persuade him to submit an application, as it were, he had declined to do this.

One example of a contemporary Staveley in Ireland has been provided by my daughter Rosalyn. She has a friend, a professional violinist, who knows a David Staveley, an Irish musician.

I had hoped that I might find information bearing on a possible connection between the Staveleys and the Harewood estate in that monumental work ‘The Victoria History of the Counties of England’, but in spite of its title it is still not complete, and the required volume (or group of volumes) on the West Riding of Yorkshire has yet to be published. If alphabetical order played some part in the planning of the History, then Yorkshire West Riding might well come last. Volumes on the North and East Ridings and on York itself have already appeared.

An Australian Connection

In the late nineteen-thirties, my brother Geoffrey reported meeting a group of R.A.F. officers, one of whom was a young Australian called Stavely (he used the one-E version), who seemed to be delighted and surprised to encounter an English Staveley. He told Geoffrey that he had met a Tony Staveley of the Coal and Iron Company, and that Tony’s mother had shown him a family Bible containing the following entry:- ‘Aloysius James Staveley, sent to Australia in 1741 for cheating at cards’. He said that one of his ancestors was so named, and that therefore he should be regarded as being on the black sheep side of the family.

The Staveley coat of arms

In the village of North Stainley, which is about five miles north- north-west of Ripon on the A6108, there is a public house called The Staveley Arms. Joyce (my wife) and I discovered this by chance about twenty years ago. Unfortunately, we arrived well before opening time, otherwise we would have gone in and made enquiries about the origin of the pub and about the Staveley family. The motto was not ‘Fidelis ad urnam’, but a better known pair of words ‘Nil desperandum’ or ‘never despair’

Published references to Staveleys

Although the part of Yorkshire with which the Staveleys have been most closely associated is the West Riding, references are made to them in the volumes on the North and East Ridings in the Victory History of the Counties of England. The earliest mention I have found of members of the clan is that roughly seven hundred years ago Staveleys were among the under-tenants of the Manor of Bishop Burton, a village about three miles west of Beverley. A William Staveley held land there in 1284/5, and John Staveley in 1302/3. I suppose it is a reasonable inference that at least these men had risen above the level of serfs. About 1660, some Staveleys belonged to a group of Quakers active in or near Hull. There is a cryptic reference to one Lord Frescheville (whose name might suggest a character in a bedroom farce but who was, in fact commander-in-chief of the forces stationed in York in 1667) as being also the First Baron Staveley. In the church of All Saints at Hunmanby (about three miles south-south-west of Filey) there are monuments to a Staveley family covering the period 1742 to 1771.

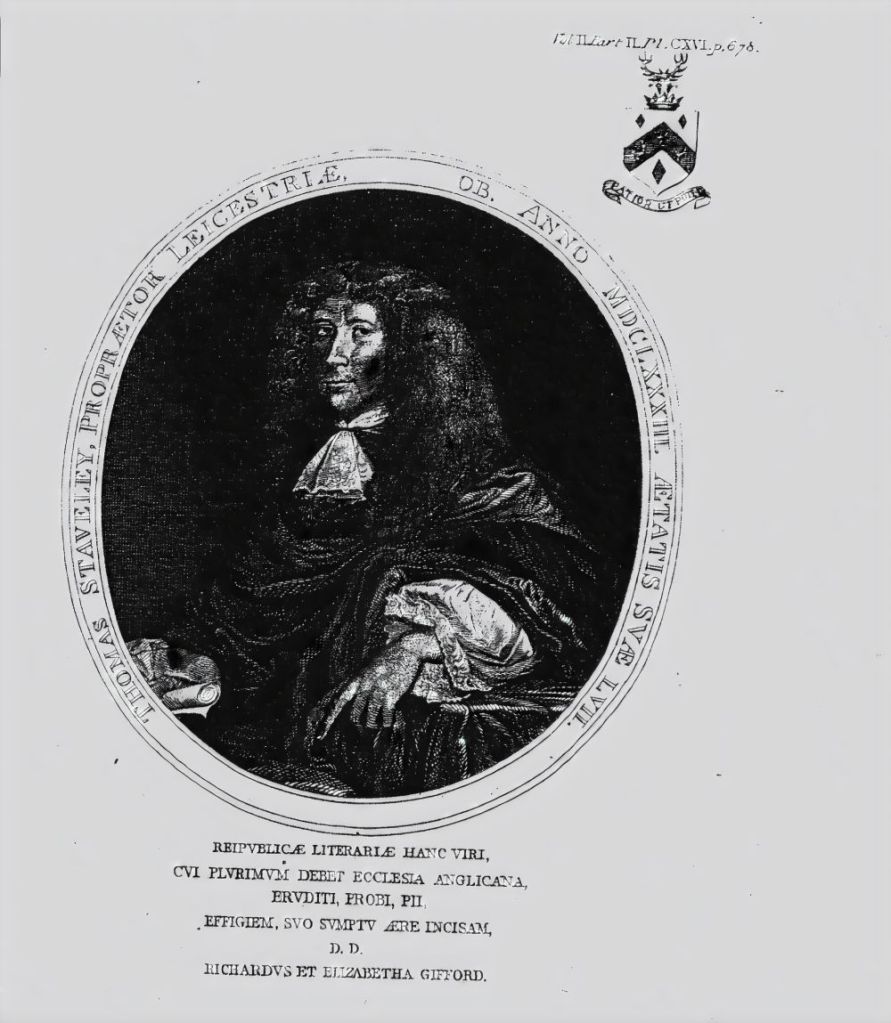

Ten years or so ago, I purchased at an antiquarian book-fair and for the trivial sum of 20p, a print of a Thomas Staveley. The print is almost certainly based on a monument in a church and was probably taken from a book on ecclesiastical history published in the eighteenth century. This Staveley was born in 1626 and died in 1684. A Latin inscription records that he was a ‘propraetor’ of Leicester, and that he was a learned and upright man to whom the Church of England owed much. But the really interesting thing about the print is that it includes a coat-of-arms which is identical with that on the inn-sign at the public house at North Stainley. On the print the three stag’s heads are delineated more clearly than on the inn-sign, and the motto is different. It takes the form of a ‘Patior ut Potiar’, ‘I endure in order to gain’ Latin pun.

There are three Staveleys in the Dictionary of National Biography (which I shall abbreviate to DNB). The first of these in time is this Thomas Staveley. He is described as an antiquarian and historian. He was born at Cossington, a village about six miles north of Leicester, where his father, another William, was rector. Thomas, who spent most of his life in or near Leicester, was a Justice of the Peace, and also Steward of the Courts of Records. He wrote several books, one being a History of Leicestershire, which (quoting the DNB) ‘included a curious pedigree of the Staveley family drawn up in 1682’. This book could probably be found in the British Museum (or maybe in the National Library), and perhaps also in the archives in the main library in Leicester. Thomas was buried in St. Mary’s Church in Leicester.

My brother Martin recently sent me a transcript of a letter which had appeared in an exhibition in Bath relating to various aspects of correspondence in past centuries. The letter was written by a Staveley from London to his brother Thomas in Leicestershire, its chief purpose being to inform his brother that he and his wife and children had survived the Great Fire of London (1666) without any harm coming to them. There can be little doubt that the recipient of this letter was the Thomas Staveley of my print.

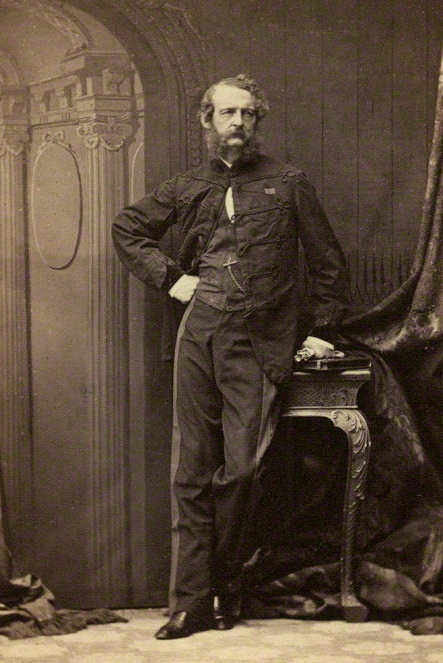

The second Staveley entry in the DNB is a soldier, William Staveley (1784-1854). His father is stated to have been ‘William Staveley of York’, who might well have been an ancestor of the Tonbridge School master Tom Staveley, since the latter’s family tree began with the entry “William Staveley, artist, of York, b. 1760′. William (the professional soldier) served under Wellington throughout the Peninsular War, and was on his staff at Waterloo. In the later stages of this epic battle, Wellington’s army was joined by the Prussian army under Field Marshal Blücher. During the battle, Wellington wished to contact Blücher, partly to report on how the battle was progressing, but also, no doubt, to enquire when Blücher’s troops might be expected to reach the battlefield. The officer chosen to ride to Blücher with Wellington’s message was William Staveley. The rank he finally reached in his military career was Lieutenant-General.

William had a son, Charles (1817-1896), who too was in the army. He served in the Crimea and in China, attained the rank of General, and was knighted. He spent his last years in the town beloved of retired army officers, namely Cheltenham. It is quite likely that this line of soldiers has continued down to the present day. The current edition of Who’s Who gives a Major-General Robert Staveley, born in 1928 and the son of a soldier.

My mother’s ancestry. The Cleobury family

There is not much information about my mother’s lineage, and what there is is almost entirely of the word-of-mouth variety. The subject is best approached by beginning with her parents and then proceeding backwards in time. There is little that I can say about her father. His name was Alfred Shepherd (whence my second Christian name), and before he married he was in the Royal Navy, in which he reached the rank of Petty Officer. Apparently his wife to be, Emma Cleobury, refused to marry him until or unless he left the navy, so probably when they were married she was about thirty and he somewhat older. My mother, their only child, was born in 1884 (and died on her eightieth birthday). Unfortunately, only a few years after this her father contracted pulmonary tuberculosis, then commonly called consumption, and he died about 1890. My mother said she could just remember walking with him when his illness must have been far advanced, for she said he had to stop every few yards to rest against a wall or railings, gasping for breath. She described him as having been strongly built and a good swimmer, who in his navy days had just missed being selected to go on an Arctic expedition. He had visited the Indian Ocean, and some of the souvenirs he brought back from that part of the world are still in existence within the family.

My mother’s mother was the only one of my four grandparents whom I actually knew. She was born about 1850 in the small town of Broseley in Shropshire, about two miles from a place which, though no larger than Broseley, is much better known by virtue of its association with the

beginning of the industrialization of Britain, namely Ironbridge. Her maiden name was Cleobury, which, like Staveley, is a place-name. Between Bridgnorth and Ludlow there is Cleobury North, and a few miles south-west of this lies Cleobury Mortimer. The ‘Cleo’ probably, but not certainly, has the same origin as Clee, a name applied to more than one village and to more than one hill in that part of Shropshire.

Emma Cleobury was the only girl in the family, but she had several brothers, one of whom was drowned at the age of seventeen in the river Severn. When and where she met Alfred Shepherd, and when she moved to London, I do not know. She lived well into her eighties, and when she was in her seventies she left London and came to live with us in Stamford, at a time when we occupied the three-bedroomed house. She always wore black or at least dark clothes, with skirts almost down to the ground, and when she went out she sported a black bonnet. So her appearance corresponded closely to the mental picture many people would now have of a Victorian widow. I cannot recall a single occasion when she spoke to me and my brothers about her husband.

Once again I must admit to complete ignorance of a forbear, in this case my maternal grandmother’s father. But the position with regard to his wife, my great-grandmother, is slightly better. Her Christian name was Mary and her maiden name was Oswell. Joyce and I possess two articles which belonged to Mary. One is a sampler which she had worked. It is about eighteen inches square, and now, alas, has faded to near- illegibility. On the upper part is the alphabet and numbers to eighteen, which seemed to be almost obligatory on samplers of the period. On the lower part there is a somewhat stylized house, flanked by trees, plants and birds. In the middle there is this verse:

Firm as the earth they gospel stands,

My Lord, my hope, my trust,

If I am found in Jesus hands

My soul can ne’er be lost.

Underneath the verse is the following:-

Mary Oswell aged 13 April 20th 1835

So Mary was born in 1822. This sampler conjures up with me a rather touching picture of this girl, little more than a child, working diligently on the sampler, probably often by candlelight. Perhaps this was the only form of diversion allowed her on Sundays.

The other article of hers which we possess is an oak chest. She must have been married in the eighteen-forties, and the oak chest was one of her wedding presents. Whether it was then new or not I don’t know, but it is interesting in having inside it, near the top, a small lidded box, presumably for money and valuables like jewellery. Also, the lock system is such that the chest is locked simply by dropping the lid. At a time when people made little use of banks (or indeed no use at all) for safeguarding their money and valuables, presumably the procedure for dealing with a threat of imminent theft was to put them in the little box in the chest and simply drop the lid.

Some fifteen years ago Joyce and I visited Broseley and went to the church. Unfortunately, it happened to be the worst day and time for conducting any serious research and enquiry – a Sunday morning when the service was about to begin. Nevertheless, one of the churchwardens found time to tell us that he believed that there was an elderly Miss Cleobury still living in Broseley. In the churchyard, a number of tombstones had been removed from graves and propped up against a wall. One of these, though rather badly defaced, clearly carried the name of Cleobury.

One of the several brothers of my grandmother Emma had a son named Frank. So he, Frank Cleobury, and my mother were first cousins who did, in fact, keep in touch over the years. Frank was a Civil Servant for a considerable time, reaching the position of Principal in the Foreign Office, but in middle age he left the Service and was ordained priest in the Church of England. The present Director of Music at King’s College, Cambridge, and hence the man responsible for its famous choir, is Stephen Cleobury, a grandson of my mother’s cousin Frank. This piece of information may prompt the reader to wonder what relationship he or she has to this distinguished musician. If so, the problem of evaluating what number of cousin he is and how many times removed is (as textbooks sometimes say) left as an exercise for the student.

While I have deliberately avoided reporting on the activities of living members of the families discussed in this article, I cannot refrain from mentioning that at the present time the Cambridgeshire Youth Orchestra contains both a Cleobury and a Staveley. The Cleobury, a violinist, is a daughter of Stephen Cleobury, while the Staveley is Richard, a grandson of my brother Alan, who plays the trumpet. These two young musicians therefore have a pair of great-great-great- grandparents in common.

One of Oxford’s legendary figures is a Dr. Martin Routh. Famed and respected for his scholarship and his personality, he died in the middle of the nineteenth century at the age of 99, having been President of Magdalen College for 63 years. Towards the end of his long life he was asked to suggest just one maxim which could serve as a rule for life. Perhaps it might be expected that the reply would be something like ‘say your prayers daily’, or ‘avoid alcohol’ or ‘have a cold bath every morning’. In fact, the old man pondered for a moment, and then said, ‘Sir, you will find it a very good practice always to verify your references’. In words of one syllable, I take this to mean ‘be sure you get your facts right’, and I like to think that I have done my best to do this in what I have written so far. I have, however, dredged up from the depths of my ageing memory two other items relevant to my subject, which I have not had the opportunity of verifying. Neither is of much importance, but both, I think, are milding interesting, so, protected by my caveat, I have decided to include them.

The first item is that about forty years ago I came across in an American scientific journal, a paper, one of the authors of which presented himself as Homer P. Stavely (with one E). I find it impossible to believe that any Staveley (or Stavely) born in England would have been christened Homer, so I can only conclude that this part-author came from an already well-established American family, which points to emigration by one or more members of the clan to the U.S.A. in the nineteenth century, or even earlier.

The second unverified recollection relates to a fictitious Staveley. I recall finding a novel, which I think was one of Trollope’s numerous works, in which one of the characters is a Miss Staveley. She is responsible for one of the chapters being headed ‘Miss Staveley declines to eat minced veal’ – or perhaps it should be ‘declines to take minced veal’!

Finally, I must thank Joyce and my brothers for the help they have given me, without which this admittedly somewhat desultory and fragmentary article would have been still more desultory and even more fragmentary.

Dr L A K Staveley

February 19, 1990.

A Supplement to a Tale of Two Families

1. Introduction

On December 28th, 1989, Joyce and I celebrated our Golden Wedding. We were touched and delighted to receive from Rosalyn, John, and Anthony and Evelyne a present the nature of which came as a complete surprise. It was, in fact, a professional report prepared by Windsor Ancestry Research on the ancestry of the Kelhams (Joyce’s forbears) and the Staveleys. In both cases, this work (which from now on I shall refer to as ‘the Report’) greatly adds to our knowledge of our ancestors. In what follows, I have attempted to extract and present the most interesting pieces of information in the Report about the Staveleys.

The following are the components of that part of the Report which deals with the Staveleys.

(a) There are four pages in which the history of our own branch of the Staveleys is discussed, and taken back to about 1720.

(b) The writer of the Report made use of that part of a modern compilation of recorded baptisms and marriages which deals with the County of York. It seems that the two chief sources of material for this compilation were the civil registration system inaugurated in 1837, and the International Genealogical Index (or I.G.I.) which began before 1837 and continued to about 1870. The I.G.I. deals chiefly with baptisms, but provides some information about marriages. The Report contains no less than 21 photocopied pages from this compilation which have over a thousand entries in the name of Staveley (or Stavely) in the County of York. These entries are presented alphabetically in Christian names, and most are dated between 1700 and 1850, though there are a few (possibly derived from wills) with dates in the seventeenth century, and one in 1540. Our branch of the family has long regarded Samuel as a traditional Staveley name, but it only provides fifteen entries, the earliest being dated 1667. The most popular male Christian name is William, which is responsible for more than one hundred entries.

(c) The writer of the Report discovered a book on the Staveleys privately published by (or for) the American members of the clan. Copies of eighteen pages of this book, which I shall refer to as ‘the American Study’, are included in the Report. On two of these pages there is a handwritten note, the first of these being ‘presented to the Society of Genealogists, Chaucer House, Malet Place, London W.C. by Fredk. W. Stavely, March 20, 1969′. The second note is as follows; ‘Each of us has inherited and enhanced some of the good qualities of our environment and heredity from our ancestors, and these we pass along to generations yet to come’. This is also signed Fredk. W. Stavely, and stamped under his signature is his address – 208 Overwood Rd., Akron, Ohio.

The American Study contains five genealogical trees, the headings of which are the Staveleys of Cork, the Staveleys of Antrim, the Staveleys of Stainley Hall, the Staveleys of North Anston, and the Staveleys of Bridlington. The Report also includes eight pages copied from the American Study which deal with various aspects of the history of Staveleys, and two more pages from the same source are devoted to the coat of arms.

(d) Finally, the Report contains a copy of two pages from Burke’s Peerage and Baronettage dealing with the house of Harewood (i.e. the Lascelles family).

In the following pages, Section 2 discusses the extension of our own pedigree, and Sections 3 to 7 survey the more interesting points which emerge from the five pedigrees in the American Study, taken in the order given above. Section 8 deals with what might be called the Lascelles

2.The extension of our family tree

With the information provided by the Report, the pedigree of our family can be taken back from the birth of Samuel Staveley to about 1720. Samuel’s bride Esther had the unusual surname of Snowball. (In some references to the birth of her later children her Christian name is given as Hester). They were married on Aug. 1, 1820 at Weaverthorpe, and their first child Jane, who died in infancy, was christened in the same village on Nov. 26, 1820. They were to have eight more children, all of whom were baptized at Harpham.

This kind of sequence had already been followed by Samuel’s parents, Michael and Penelope. They were married at Nafferton on Jan. 1, 1776, and their first child was christened there on July 17, 1776. Their other six children were baptized at Harpham. Anyone casting a disapproving eye on the pre-marital activities of earlier Staveleys, however, should not be too censorious. After all, at that time one could not just drop into the local tavern and extract a packet of condoms from the slot-machine in the lavatory.

Samuel was far from being an only child. He had four brothers, and it is obvious therefore that if there are Staveleys alive today who are descended from these brothers, then they are our nearest Staveley relatives. Samuel’s uncles on his father’s side may also have provided descendants. However, tracing such lines of descent to the present day could be far from easy. The invaluable tables included in the Report are not only limited to the County of York but chronicle chiefly baptisms. Fewer marriages are recorded, and deaths not at all. Thus, there is no reference to Samuel’s eldest brother Isaac other than his baptism. He might have died young, or never married, or, of course, he might have left Yorkshire, as Samuel did.

To take a further step backward in time it will be necessary to discover the parentage of the Isaac Staveley who was probably born between 1715 and 1725. This period is more or less on the limit of the I.G.I. The writer of the Report points out that a search should be made for Isaac’s baptism in parish records, adding encouragingly ‘Prospects for further research are good’. I found from the Report that there was a Robert Staveley in Kirkburn who had a daughter who was christened Ann on Feb. 11, 1711, and a son Richard baptized on Oct. 4, 1713. So it is possible one cannot say more than that – that Robert also fathered Isaac, but that for some unknown reason the baptism was not included in the County of York compilation. If this is true, then since Robert Staveley would probably have been born between 1680 and 1690, the pedigree would now cover three hundred years.

3.The Staveleys of Cork

The first five lines of this pedigree are shown in Appendix 3. They have been carefully copied to be exactly as presented in the American Study, because they contain a fact which, if true, is quite extraordinary, namely that the William Staveley who went to Ireland lived to be 118. The same year of his death (1748) is given in the pedigree of the Staveleys of Antrim, where it is added that he went to Ireland between 1638 and 1655. Another remarkable feature of this part of the pedigree given in Appendix 3 is the appearance of the name Lascelles. This will be discussed in Section 8.

The pioneer émigré to Ireland, William, had two sons, Joseph and William. It is not known which was the older, and which therefore is to be regarded as the founder of the senior branch of the Irish Staveleys.

However, while William remained in or near Kells in Co. Antrim, Joseph went south after marrying and established the Cork branch. The Cork pedigree descends through a series of eldest sons all of whom were christened Robert. Two of them, namely Robert III (b. 1795) and Robert VI (b.1892), are noteworthy in that both of them, and especially Robert VI, made a serious study of Staveley history. Much of the history in the American Study is the outcome of the investigations of Robert VI. The main male line appears to have ended with him. In 1923, he married Ilys Evelyn Sutherland. They had no son, but one daughter, Evelyn Ilys, (b. 1925). But at some stage in the male line which stage is not clear – there must have been a return to England, since in the American Study there is a passage, almost certainly originating with Robert VI himself, which ends with the following sentence: “The Family History is largely the result of the efforts of Robert Staveley III and Robert Staveley VI (1928) of Merton Lodge, Headington, Oxford, and of Mrs. Cecil Staveley of Cosmore Farm, Middlemarsh, Sherborne, England, who was the wife of Admiral Cecil Staveley of the British Navy’.”

It should be pointed out that the pedigrees presented in the American Study are generally only concerned with the main male line, and give no information about collateral descents. So even if one of the Roberts did return to England, some Staveleys were no doubt left in or near Cork. In the American Study there is only one sentence about them as a group, which is as follows: “The family in Cork was important and a respected one where it continued for nine generations, many of whom were very well educated and distinguished in their respective fields’.

There is a brief reference to the Admiral on page 8 of my article ‘A Tale of Two Families’.

(4) The Staveleys of Antrim, and later of the U.S.A.

This genealogical tree is given in much more detail than that used in the previous Section. The first three lines are essentially the same as those of the Staveleys of Cork pedigree, but thereafter it deals with the descendants of William (Joseph’s brother). This William settled at Ferniskey, near Kells and Connor, Co. Antrim, where he acquired some property which remained in the family for at least four generations. He and his wife are said to have died of fever on the same day, and to be buried in the churchyard of Connor Cathedral. William had a son, Aaron, and also two daughters who, probably after marriage, appear to have started the emigration of members of the family to America. Aaron was followed by three Williams, the third of these, Aaron’s great-grandson, being the last William in the pedigree. He was born in 1812, married in 1840, and in 1842 he left Ferniskey for the U.S.A., where he died in 1899. The change in nationality was accompanied by a change in the family surname to the one-E version. Among the grandchildren of this last William is a Frederick W. Stavely (b. 1894), who was surely the Fredk. W. Stavely mentioned in the introduction as being the man behind the American Study. He could justly claim that his known ancestry went back nine generations to the Robert Staveley who died leaving a widow who married a Lascelles. Frederick had one son, Robert Thomas (b. 1931), who in turn had (or has) two sons with whom the pedigree in the American Study ends, namely Frederick Allan (b. 1956) and Brian (b. 1960).

It is sometimes possible to buy a one-page family history for a particular surname. The way that such brief articles are presented, (they tend to be padded out with a little general English history), suggests that they are intended to catch the eye of visitors from overseas with that surname. I have a copy of such an article on the Staveleys, for which I am indebted to my nephew Peter. In addition to Staveleys who migrated to America from Ireland, there can be little doubt that some of the clan went directly from England to the New World, and it is probable that the following extracts from this one-page article applies to migration from England. ‘Members of the family sailed aboard the huge armada of three- masted sailing ships known as the ‘White Sails’, which plied the stormy Atlantic. These overcrowded ships were pestilence ridden, sometimes 30% to 40% of the passenger list never reaching their destination. In North America, migrants included Elizabeth Staveley, landed in America in 1760; John Stavelie, settled in Philadelphia, Pa., 1834; Edward Stavely, settled in New Castle, Del. in 1839; John, Richard and Robert Stavely, settled in Nova Scotia in 1774.”

(5) The Staveleys of Stainley Hall

In my previous article, Stainley Hall was mentioned as a result of the chance discovery of a public house in the village of North Stainley, near Ripon, called the Staveley Arms, which has the Staveley coat of arms on its inn-sign. In the pedigree of this branch of the clan the most popular name for the heirs is Miles, which occurs six times in thirteen generations, while William only makes three appearances. Some less common names in the pedigree are Ninian, Sampson, Marmaduke and Basil. The tree starts about 1500 and side-steps, as it were, early in the nineteenth century. The tenth generation was headed by General Miles Staveley (1738-1814). He left no issue, and bequeathed the Stainley Estate to a grandson of a cousin, a Capt. Hutchison (1780-1860), at some time M.P. for Ripon. Hutchison changed his name to Staveley, but his only son died at the age of fourteen, and the estate passed to a daughter who never married. She died in 1941, leaving a will which transferred the property to a William Miles Staveley (b. 1913), whose origin is not made clear. There is a passage about Stainley Hall in the American Study in which the ubiquitous Fredk. W. Stavely appears again, which is as follows: “The current occupant is Capt. William Miles Staveley, who was most gracious in showing Fredk. W. Stavely pictures of some of the early occupants. This is the third residence on this site’. The present house is probably early Victorian. The estate covers about a thousand acres.

(6) The Staveleys of North Anston

I am not sure where North Anston is. There is an Anston roughly midway between Sheffield and Worksop. The pedigree is relatively short (ca. 1700-1850), and not particularly interesting. The name given to the eldest son was Francis. A Lieut. Francis Staveley was killed at Badajoz in the Peninsular War, and one of his brothers is entered as ‘John Staveley- Shirt of Harthill, assumed the name of Shirt’ – surely a retrograde step. A William Staveley emigrated to Australia in about 1850.

(7) The Staveleys of Bridlington

If one had to associate our own branch with one of the five considered in Sections (3) to (7) the obvious choice would seem to be the Bridlington branch on geographical grounds. But not a single place is named in the Bridlington pedigree (the work of Robert Staveley VI of Section 3), and there is nothing to suggest a link between this tree and the Staveleys of the villages near Great Driffield. The pedigree starts about 1500 with Robert Stayfley, and his son Richard is given the same surname. After that, beginning with Robert Staveley (b. ca. 1545) it is Staveley all the way. In the fourteen generations listed, Richard is the preferred Christian name, appearing seven times, with William as the runner-up. The male line is unbroken, and ends with Delwyn C. Staveley (b. 1898), which of course implies that we are now in the U.S.A., or at least a long way from Bridlington. At a guess, emigration of an eldest son in this branch could have started early in the nineteenth century. Sometime in the second half of the previous century a younger son, Luke by name, had started a branch in Halifax presumably the Halifax of Yorkshire rather than that of Nove Scotia.

(8) The Lascelles legend

In my article ‘A Tale of Two Families’, I summarized a story which had reached me in a letter from a New Zealander, according to whom a Staveley had died leaving two young sons and a widow who had then married a Lascelles. The sons had been deported to Ireland, and it was believed that in this way the Lascelles family (later to provide the Earls of Harewood) had thereby acquired property which really belonged to the Staveleys. Information provided by the Report shows that at least the story is not complete nonsense, though it is still not possible to say unambiguously what really happened. According to the beginning of the pedigree in Appendix 3, a Robert Staveley who died in 1638 left a widow who later married ‘Lascelles’, and a son William, born in 1630. This information is repeated in the pedigree discussed in Section (4). That only one son is mentioned in the pedigree does not exclude the possibility that there was a second son. In the extract in the Report from Burke’s Peerage and Baronettage the following entry appears in the section headed Harewood: ‘Francis Lascelles, of Stank and Northallerton ….. b. 23 Aug. 1612, m. Frances (bur. 20 Sept. 1658), dau. of Sir William Quinton, 1st Bt. of Harpham, co. York’. The date of the marriage is not given, but they had a son born in 1655. So, from the dates, it is quite possible that Robert Staveley had married Miss Frances Quinton of Harpham, who, after her husband’s death, became Mrs. Lascelles, though this cannot of course be regarded as proven. It may be just coincidence that Harpham is where years later numerous Staveleys of our own branch were to be born. But if, in fact, Frances did marry Robert Staveley, he might well have lived in or near Harpham.

These events took place about a century before Harewood House as we know it was built. The Sunday Times of April 8, 1990 devoted most of the magazine to listing the wealthiest people in Britain. Each entry took the form of a photograph accompanied by a biographical note. The present Earl of Harewood appeared in this survey, his estate being valued at £50 million. The biographical note began as follows: ‘Henry Lascelles, having made a fortune from the slave trade, bought the Harewood estate outside Leeds in 1738, and commissioned the house, now regarded as one of England’s great treasures’.

(9) Some comments on the early history of the Staveleys and on their distribution in England

The author of the text of the American Study who was perhaps Fredk. W. Stavely himelf – supplied some interesting information about the Staveleys in medieval times, mostly based on property records. The Staveleys began, so to speak, in Westmorland (now Cumbria), Yorkshire, Lancashire, Cheshire and Derbyshire, settling in places roughly on the same latitude. Much of the land they possessed was originally given by William the Conqueror to his relatives, friends and supporters. This seems to have been the case, for example, with Adam de Staveley (d. 1218), who owned a large amount of land in the above regions. The discussion in the American Study of Adam’s ancestry is not very clear, but evidence obtained from the Cumberland and Westmorland Archaeological Society seems to imply that Adam was a descendant of Earl Alan Fergant, who commanded the rear of the Norman army at the battle of Hastings (1066).

Alan had no son, and on the marriage of his daughter Alice his estates passed into other hands. References to Staveleys as property owners are encountered down to about 1620.

In Derbyshire, the first recorded member of the clan was Richard de Staveley in 1187. In 1264 another Richard (perhaps descended from the former) was granted a pardon for murder on the condition that he and his collaborators would stand trial if called upon to do so. In 1305, a Richard de Staveley, possibly the pardoned murderer, was himself murdered by one Nicholas de Matlack, who was later pardoned for his crime. Several Staveley families lived in Derbyshire, at least until towards the end of the eighteenth century.

Information about the Cheshire Staveleys begins about 1200 with Simon de Staveley. These families were connected with Staveleys in Lancashire and Derbyshire, and descendants can be traced down to about 1780. The outstanding Cheshire Staveley seems to have been Ralph de Staveley, who was around in 1457 and who was sometimes referred to as Lord Staveley. His daughter married Sir Thomas Ashton, and as a result the manor of Staveley passed to the Ashton family. For a time, Leeds was a centre for Staveleys, but the records of burials, while fairly numerous, fall in the rather limited period of 1624 to 1722, suggesting movement away from Leeds.

Migration to southern counties began quite early. In my previous article, brief mention was made of a William Staveley who is commemorated by a brass dated 1498 in the church at Bicester. He undoubtedly came from Yorkshire, and was a man of considerable wealth and influence. His family, however, does not appear to have expanded in Oxfordshire or neighbouring counties, but rather to have moved north into Leicestershire. Reference was made in my earlier article to a Thomas Staveley who lived in or near Leicester in the seventeenth century. He was a historian, and one of the three Staveleys to be found in the Dictionary of National Biography. A Staveley family moved from Yorkshire to Devonshire in about 1500, settling in East Buckland, near Barnstaple. Descendants are almost certainly to be found in the county today, as I was once asked when I was an undergraduate (though this was admittedly a long time ago) if I was ‘one of the Devonshire Staveleys’. From wills made in the seventeenth century, Staveleys were associated with Exeter, Sidmouth, West Buckland, and also with a place given in the American Study as Sideford, which might be a mis-spelling of Bideford, or of the village of Sidford, near Sidmouth.

Two cities with which Staveleys were closely associated in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries were Ripon and York, especially the former, where Staveleys appear to have become numerous and prominent quite early in the fifteenth century, well before they took up residence in Stainley Hall some four miles from Ripon. They held land near Ripon (apart from the estate at North Stainley), and were active in civic affairs, as is illustrated by the clan providing the Wakeman of the city three times, in 1447, 1463 and 1531. It is gratifying to note that each of the three Staveley Wakemen were given the appellation ‘Gent’.

In York, some of the Staveleys were merchants, and, as in Ripon, they were prominent in civic administration. For example, one Alan Staveley, who had been made a freeman of the city in 1494, was Lord Mayor in 1514 and 1515.

(10) The Staveley Coat of Arms

This side of Staveley history begins in the reign of Edward III, but the earlier coats of arms differed from what might be called the later established version. The American Study contains a drawing of this.

Until the seventeenth century, the Wakeman in Ripon was the leading official. The ‘Wakeman’s House’, dating from the thirteenth century, still exists, as does the custom of blowing a horn at 9p.m. every night – the ‘Wakeman’s Horn’.

version which is essentially the same as that depicted in my previous article. It has almost certainly been taken from Burke’s Landed Gentry and bears the motto ‘Nil Desperandum’. The earliest recorded date for it is 1531, when it was displayed by the Devonshire Staveleys, who had probably brought the coat of arms with them when they left Yorkshire. Other places or districts associated with Staveleys who sported this coat of arms include Stainley Hall, Dublin, Oxford, London and Cheshire. There are two specimens to be seen in the windows of Stainley Hall, and three in Ripon Cathedral, and of course there is the inn-sign of the Staveley Arms at North Stainley which was used for the drawing in my previous article.

The Staveley coat of arms consists of three red lozenges on a white background, and three bucks heads on a blue chevron. In heraldry, white or silver denotes peace and sincerity, lozenges represent honesty and constancy, while bucks symbolize purity and fleetness. It would appear that self-advertisement was not wholly absent from the minds of the Staveleys when they designed or chose their coat of arms.

Dr L A K Staveley

Dec. 18th 1991.

APPENDIX 2

Kirkburn, Kilnwick, Bainton and North Dalton form a group of villages on the wolds a few miles south-west of Great Driffield and about the same distance north-west of Beverley. Kirkburn is on the A163 about four miles from Great Driffield, and the same distance north of Kilnwick. Bainton is on the B1248 to the west of these two villages and about equidistant from both of them, while North Dalton is two miles west of Bainton. Nafferton and Harpham are on the opposite side of Great Driffield. Nafferton is on the A166 (the road to Bridlington) about two miles from Great Driffield, and also on the railway line between the two towns. Harpham is also on the A166, roughly midway between Bridlington and Great Driffield. Weaverthorpe is about ten miles north of Great Driffield on the west side of the B1249, while Leven is about six miles north-east of Beverley on the A1035.

Two villages in particular, Kirkburn and Kilnwick, have been closely associated with the family, and it would not be surprising to find Staveleys living there now. The references to both villages in the County of York register cover nearly a century and a half, from 1711 to 1858 for Kirkburn and from 1736 to 1876 for Kilnwick. There is a curious point concerning the two villages which I cannot explain. In the twenty-one photocopied pages from the County of York register, there are fourteen baptismal entries giving Kirkburn as the relevant place which are immediately followed by another entry identical in every way except that Kirkburn has been replaced by Kilnwick.

Bainton has a fine fourteenth century church, while that of Kirkburn is Norman and said to be ‘remarkably interesting’. It certainly could be to a Staveley if the parochial records for the last three hundred years or more still exist. Weaverthorpe also has a partly Norman church.

Note: When this research was originally carried out there were no automated websites that would locate and find documents for you. Everything was done by the examination of records in a painstaking process which was not always 100% accurate.